Imagine being picked off the street, told you committed a murder you know nothing about, and sentenced to 20 years in prison during Kafkaesque trial proceedings with no judge or jury present.

In 2005, this happened to Toño Zúñiga, in Mexico City. Mr. Zúñiga was lucky that two young lawyers obtained a retrial, videotaped it, and made a hit documentary with their footage. When Cinépolis and Televisa put “Presumed Guilty” on cinema and television screens in Mexico, many legal professionals excitedly pointed out that a judge was present in the film’s courtroom, when–owing to the written nature of the proceedings–judges usually weren’t.

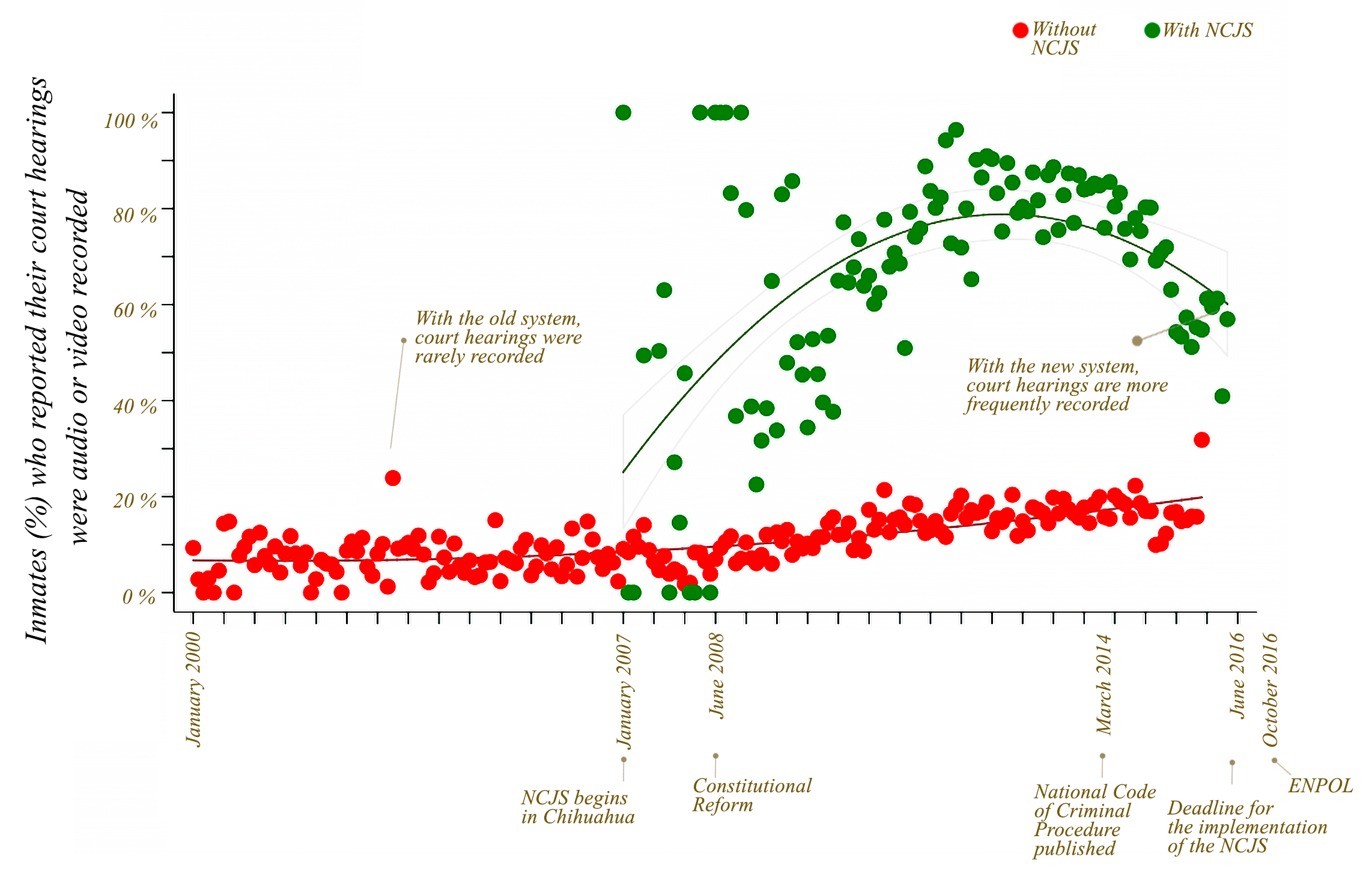

The film solidified the desire for audio and videotaping of trials as a matter of public policy, and helped galvanize the impetus of earlier reformers who had advocated for the adoption of presumption of innocence and an adversary trial system. The old justice system began being phased out at the municipal level and by type of crime as early as 2007. However, roughly half of the municipalities implemented the new system (the New Criminal Justice System, or NCJS) between mid-2015 and June 2016, which was the implementation deadline for the nation.

The World Justice Project (WJP) is now evaluating the changes in crime investigation, prosecution services, and trial procedures under the NCJS. As a first step in this evaluation, the WJP analyzed data from the first National Inmate Survey (ENPOL 2016) conducted by Mexico’s National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI). This survey was administered to almost 60,000 inmates, and it allows testing the NCJS performance from the user’s perspective and experience.

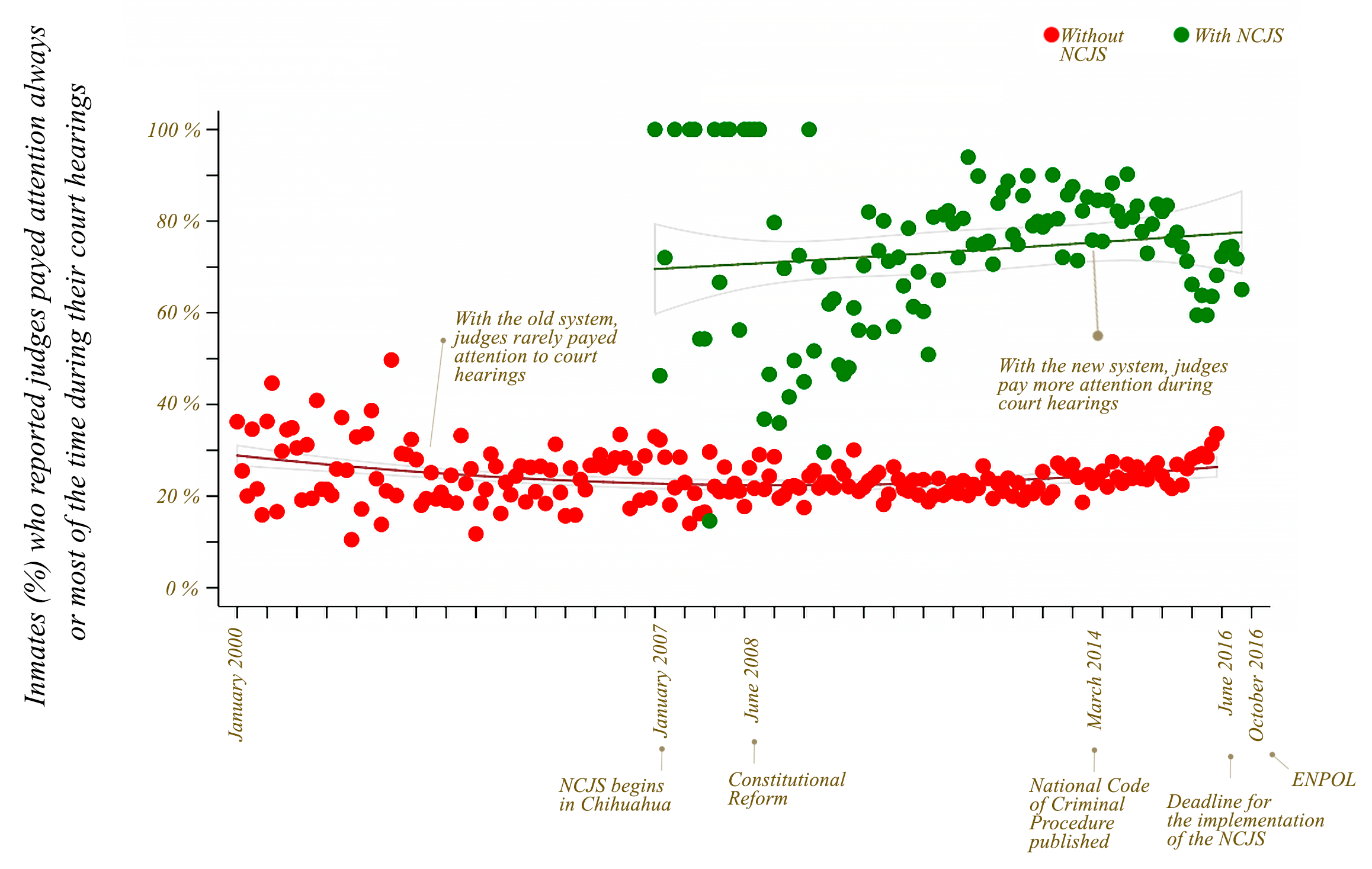

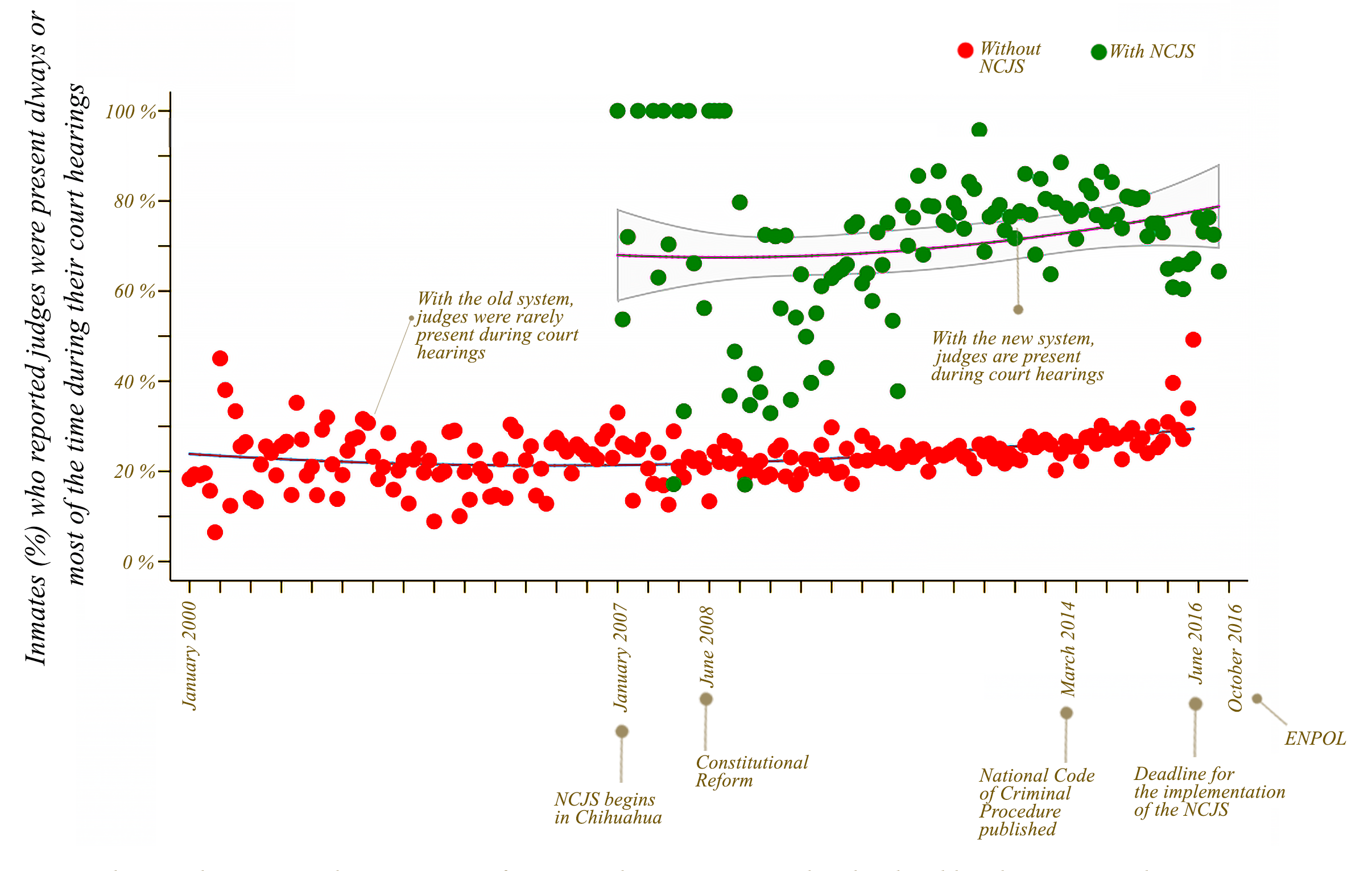

Prisoners were asked whether there was a judge present in the courtroom; whether the judge was paying attention to the proceedings and whether the court proceedings were audio or video recorded, among hundreds of other questions.

WJP created pre- and post-reform groups of inmates using combined data from the inmate survey with the implementation dates of the new justice system at the municipal level. The following charts compare the experiences of inmates tried before and after the reforms were put in place, showing a significant increase in the percentage of hearings that are audio or video recorded, along with judges being present and paying attention during court hearings.

In order to congratulate the supporters of the reforms, Mexico’s film industry, the moviegoers who supported Presumed Guilty, and the reformers who implemented the change, WJP decided to share the good news in the form of holiday cards, available in both English and Spanish. Download yours at the bottom of the page and share the good news!

With NCJS, judges are present during court hearings

With NCJS, court proceedings are more frequently recorded

With NCJS, judges pay more attention during court hearings